In the Neighborhood of Chaos

Dear Eugene,

"People are proud to be saying Merry Christmas again. I am proud to have led the charge against the assault of our cherished and beautiful phrase. MERRY CHRISTMAS!!!!!"

So said Donald Trump. Yesterday I read in a Christian magazine quoting him, saying something along the same line, about him being the savior of Christmas, if not Jesus himself. I am ashamed to say I used to write for this magazine.

I suppose I shouldn't be writing when I feel angry. Especially on Christmas day. I have no right to be angry. A Desert Father once said the only reason to get angry at a brother is to bring him closer to Jesus, and no other reason is justifiable. I need to stop writing and start praying.

Let me share with you an excerpt from Rowan Williams' masterful little book "Being Christian" on baptism. The best way to fight against the anti-Christ is to know, to love, and be like Christ.

Merry Christmas, my dear pastor. Thank you for your faithfulness in Jesus, finding me in "the neighborhood of chaos." I spent Christmas eve in a little church I grew up when I first arrived at Canada. Saw many old faces. Lives lived differently. Bittersweet. The road taken or not.

Thank you for showing me the Road to take.

Alex

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life. (Romans 6.3–4)

We begin with baptism: with the fact that people are formally brought into the Christian community by being dipped in water or having water poured over them.

The word 'baptism' originally just meant 'dipping'. If we turn to the New Testament we find this word featuring in the ministry and teaching of Jesus, and also, quite extensively, in St Paul's letters. Jesus speaks of the suffering and death that lies ahead of him as a 'baptism' he is going to endure (Mark 10.38). That is, he speaks as if his going towards suffering and death were a kind of immersion in something, being drowned or swamped in something. He has, he says, an 'immersion' to go through, and until it is completed he will be frustrated and his work will be incomplete (Luke 12.50). So it seems that, from the very beginning, baptism as a ritual for joining the Christian community was associated with the idea of going down into the darkness of Jesus' suffering and death, being 'swamped' by the reality of what Jesus endured. St Paul speaks of being baptized 'into' the death of Christ (Romans 6.3). We are, so to speak, 'dropped' into that mysterious event which Christians commemorate on Good Friday, and, more regularly, in the breaking of bread at Holy Communion.

Out of the depths

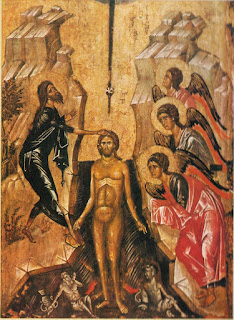

As the Church began to reflect a bit more on this in the early Christian centuries, as it began to shape its liturgy and its art, another set of associations developed. In the story of Jesus' baptism he goes down into the water of the River Jordan, and as he comes up out of the water the Holy Spirit descends upon him in the form of a dove and a voice speaks from heaven: 'You are my Son' (Luke 3.22). Reflecting on that story, the early Christians soon began to make connections with another story involving water and the Spirit. At the very beginning of creation, the book of Genesis tells us, there was watery chaos. And over that watery chaos there was, depending on how you read the Hebrew, the Holy Spirit hovering or a great wind blowing (or perhaps one is a sort of metaphor for the other). First there is chaos, and then there is the wind of God's Spirit; and out of the watery chaos comes the world. And God says, 'This is good.' The water and the Spirit and the voice: you can see why the early Christians began to associate the event of baptism with exactly that image which St Paul uses for the Christian life – new creation.

So the beginning of Christian life is a new beginning of God's creative work. And just as Jesus came up out of the water, receiving the Spirit and hearing the voice of the Father, so for the newly baptized Christian the voice of God says, 'You are my son/daughter', as that individual begins his or her new life in association with Jesus.

In the tradition of the Christian East especially, when the baptism of Jesus is shown in icons you will usually see Jesus up to his neck in the water, while below, sitting under the waves, are the river gods of the old world, representing the chaos that is being overcome. So from very early on baptism is drawing around itself a set of very powerful symbols. Water and rebirth: rebirth as a son or daughter of God, as Jesus himself is a son; chaos moving into order as the wind of God blows upon it.

So it is not surprising that as the Church reflected on what baptism means, it came to view it as a kind of restoration of what it is to be truly human. To be baptized is to recover the humanity that God first intended. What did God intend? He intended that human beings should grow into such love for him and such confidence in him that they could rightly be called God's sons and daughters. Human beings have let go of that identity, abandoned it, forgotten it or corrupted it. And when Jesus arrives on the scene he restores humanity to where it should be. But that in itself means that Jesus, as he restores humanity 'from within' (so to speak), has to come down into the chaos of our human world. Jesus has to come down fully to our level, to where things are shapeless and meaningless, in a state of vulnerability and unprotectedness, if real humanity is to come to birth.

This suggests that the new humanity that is created around Jesus is not a humanity that is always going to be successful and in control of things, but a humanity that can reach out its hand from the depths of chaos, to be touched by the hand of God. And that means that if we ask the question, 'Where might you expect to find the baptized?' one answer is, 'In the neighbourhood of chaos'. It means you might expect to find Christian people near to those places where humanity is most at risk, where humanity is most disordered, disfigured and needy. Christians will be found in the neighbourhood of Jesus – but Jesus is found in the neighbourhood of human confusion and suffering, defencelessly alongside those in need. If being baptized is being led to where Jesus is, then being baptized is being led towards the chaos and the neediness of a humanity that has forgotten its own destiny.

I am inclined to add that you might also expect the baptized Christian to be somewhere near, somewhere in touch with, the chaos in his or her own life – because we all of us live not just with a chaos outside ourselves but with quite a lot of inhumanity and muddle inside us. A baptized Christian ought to be somebody who is not afraid of looking with honesty at that chaos inside, as well as being where humanity is at risk, outside.

So baptism means being with Jesus 'in the depths': the depths of human need, including the depths of our own selves in their need – but also in the depths of God's love; in the depths where the Spirit is re-creating and refreshing human life as God meant it to be.

Sharing in the life and death of Jesus

If all this is correct, baptism does not confer on us a status that marks us off from everybody else. To be able to say, 'I'm baptized' is not to claim an extra dignity, let alone a sort of privilege that keeps you separate from and superior to the rest of the human race, but to claim a new level of solidarity with other people. It is to accept that to be a Christian is to be affected – you might even say contaminated – by the mess of humanity. This is very paradoxical. Baptism is a ceremony in which we are washed, cleansed and re-created. It is also a ceremony in which we are pushed into the middle of a human situation that may hurt us, and that will not leave us untouched or unsullied. And the gathering of baptized people is therefore not a convocation of those who are privileged, elite and separate, but of those who have accepted what it means to be in the heart of a needy, contaminated, messy world. To put it another way, you don't go down into the waters of the Jordan without stirring up a great deal of mud!

When we are brought to be where Jesus is in baptism we let our defences down so as to be where he is, in the depths of human chaos. And that means letting our defences down before God. Openness to the Spirit comes as we go with Jesus to take this risk of love and solidarity. And that is why, as we come up out of the waters of baptism with Jesus, we hear what he hears: 'This is my son, this is my daughter, this is the one who has the right to call me Father.' The Spirit, says St Paul, is always giving us the power to call God Father, and to pray Jesus' prayer (Galatians 4.6). And the baptized are these who, going with Jesus into risk and darkness, open themselves up to receive the Spirit that allows them to call God Father.

So what else do you expect to see in the baptized? An openness to human need, but also a corresponding openness to the Holy Spirit. In the life of baptized people, there is a constant rediscovering, re-enacting of the Father's embrace of Jesus in the Holy Spirit. The baptized person is not only in the middle of human suffering and muddle but in the middle of the love and delight of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. That surely is one of the most extraordinary mysteries of being Christian. We are in the middle of two things that seem quite contradictory: in the middle of the heart of God, the ecstatic joy of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit; and in the middle of a world of threat, suffering, sin and pain. And because Jesus has taken his stand right in the middle of those two realities, that is where we take ours. As he says, 'Where I am, there will my servant be also' (John 12.26).

Growing out of that, the prayer of baptized people is going to be a prayer that is always moving in the depths, sometimes invisibly – a prayer that comes from places deeper than we can really understand. St Paul says just this in his letter to the Romans: 'The Spirit helps us in our weakness ... that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words' (Romans 8.26). The prayer of baptized people is never just 'rattling off' the words at surface level. The prayer of baptized people comes from a place deeper than we can penetrate with our minds or even our feelings. Prayer in the baptized community surges up from the depths of God's own life. Or, to change the metaphor, you might say that we are carried along on a tide deeper than ourselves, welling up from God's depths and the world's.

The prayer of baptized people is a growing and moving into the prayer of Jesus himself and therefore it is a prayer that may often be difficult and mysterious. It will not always be cheerful and clear, and it may not always feel as though it is going to be answered. Christians do not pray expecting to get what they ask for in any simple sense – you just might have noticed that this can't be taken for granted! Rather, Christians pray because they have to, because the Spirit is surging up inside them. Prayer, in other words, is more like sneezing – there comes a point where you can't not do it. The Spirit wells and surges up towards God the Father. But because of this there will be moments when, precisely because you can't help yourself, it can feel dark and unrewarding, deeply puzzling, hard to speak about.

Which is why so many great Christian writers on the spiritual life have emphasized that prayer is not about feeling good. It is not about results, or about being pleased with yourself; it is just what God does in you when you are close to Jesus. And that of course means that the path of the baptized person is a dangerous one. Perhaps baptism really ought to have some health warnings attached to it: 'If you take this step, if you go into these depths, it will be transfiguring, exhilarating, life-giving and very, very dangerous.' To be baptized into Jesus is not to be in what the world thinks of as a safe place. Jesus' first disciples discovered that in the Gospels, and his disciples have gone on discovering it ever since.

One of the great privileges of my time as Archbishop of Canterbury was being allowed to go and see some of those places at close quarters where people live in dangerous proximity to Jesus; where their witness means they are at risk in various ways. And when you see people in places like Zimbabwe, Sudan, Syria or Pakistan living both in the neighbourhood of Jesus and in the neighbourhood of great danger, you understand something of what commitment to the Christian life means, the commitment of which baptism is the sign. But you see it also when you look at the lives of great saints whose path of contemplation has led them to deep inner desolation, loneliness and uncertainty (think of what Mother Teresa of Calcutta wrote in her diaries about the many years in which she felt practically no 'spiritual' comfort, only isolation and darkness). All this results from the upsurging life of the Spirit in the centre of our being, coming from the heart of God. Like the saints before us, we tread a dangerous path – which is also the path to life.

The path is both dangerous and life-giving for me as an individual believer – but not only for me. The other great truth about baptism is that it brings you into proximity not only with God the Father, not only with the suffering and muddle of the human world, but with all those other people who are invited to be there as well. Baptism brings you into the neighbourhood of other Christians; and there is no way of being a Christian without being in the neighbourhood of other Christians. Bad news for many, because other Christians can be so difficult! But that is what the New Testament tells us very uncompromisingly: to be with Jesus is to be where human suffering and pain are found, and it is also to be with other human beings who are invited to be with Jesus. And that, says the New Testament, is a gift as well as sometimes a struggle and an embarrassment.

It is a gift because in this community of baptized people we receive life from others' prayer and love, and we give the prayer and love that others need. We are caught up in a great economy of giving and exchange. The solidarity that baptism brings us into, the solidarity with suffering, is a solidarity with one another as well. It is what some Christian writers have called, in a rather forbidding word, 'co-inherence'. We are 'implicated' in one another, our lives are interwoven. What affects one Christian affects all, what affects all affects each one. And, whether as individual Christians or as individual Christian groups and denominations, we often find that hard to believe and accept. We find it hard to accept it as a gift – yet a gift is what it is. It means that the darkness that belongs in the baptized life is never my own problem exclusively. It is shared: how it is shared is very mysterious, and yet most of us who are baptized Christians can witness in one way or another to the fact that it works.

So baptism restores a human identity that has been forgotten or overlaid. Baptism takes us to where Jesus is. It takes us therefore into closer neighbourhood with a dark and fallen world, and it takes us into closer neighbourhood with others invited there. The baptized life is characterized by solidarity with those in need, and sharing with all others who believe. And it is characterized by a prayerfulness that courageously keeps going, even when things are difficult and unpromising and unrewarding, simply because you cannot stop the urge to pray. Something keeps coming alive in you; never mind the results.

"People are proud to be saying Merry Christmas again. I am proud to have led the charge against the assault of our cherished and beautiful phrase. MERRY CHRISTMAS!!!!!"

So said Donald Trump. Yesterday I read in a Christian magazine quoting him, saying something along the same line, about him being the savior of Christmas, if not Jesus himself. I am ashamed to say I used to write for this magazine.

I suppose I shouldn't be writing when I feel angry. Especially on Christmas day. I have no right to be angry. A Desert Father once said the only reason to get angry at a brother is to bring him closer to Jesus, and no other reason is justifiable. I need to stop writing and start praying.

Let me share with you an excerpt from Rowan Williams' masterful little book "Being Christian" on baptism. The best way to fight against the anti-Christ is to know, to love, and be like Christ.

Merry Christmas, my dear pastor. Thank you for your faithfulness in Jesus, finding me in "the neighborhood of chaos." I spent Christmas eve in a little church I grew up when I first arrived at Canada. Saw many old faces. Lives lived differently. Bittersweet. The road taken or not.

Thank you for showing me the Road to take.

Alex

************

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life. (Romans 6.3–4)

We begin with baptism: with the fact that people are formally brought into the Christian community by being dipped in water or having water poured over them.

The word 'baptism' originally just meant 'dipping'. If we turn to the New Testament we find this word featuring in the ministry and teaching of Jesus, and also, quite extensively, in St Paul's letters. Jesus speaks of the suffering and death that lies ahead of him as a 'baptism' he is going to endure (Mark 10.38). That is, he speaks as if his going towards suffering and death were a kind of immersion in something, being drowned or swamped in something. He has, he says, an 'immersion' to go through, and until it is completed he will be frustrated and his work will be incomplete (Luke 12.50). So it seems that, from the very beginning, baptism as a ritual for joining the Christian community was associated with the idea of going down into the darkness of Jesus' suffering and death, being 'swamped' by the reality of what Jesus endured. St Paul speaks of being baptized 'into' the death of Christ (Romans 6.3). We are, so to speak, 'dropped' into that mysterious event which Christians commemorate on Good Friday, and, more regularly, in the breaking of bread at Holy Communion.

Out of the depths

As the Church began to reflect a bit more on this in the early Christian centuries, as it began to shape its liturgy and its art, another set of associations developed. In the story of Jesus' baptism he goes down into the water of the River Jordan, and as he comes up out of the water the Holy Spirit descends upon him in the form of a dove and a voice speaks from heaven: 'You are my Son' (Luke 3.22). Reflecting on that story, the early Christians soon began to make connections with another story involving water and the Spirit. At the very beginning of creation, the book of Genesis tells us, there was watery chaos. And over that watery chaos there was, depending on how you read the Hebrew, the Holy Spirit hovering or a great wind blowing (or perhaps one is a sort of metaphor for the other). First there is chaos, and then there is the wind of God's Spirit; and out of the watery chaos comes the world. And God says, 'This is good.' The water and the Spirit and the voice: you can see why the early Christians began to associate the event of baptism with exactly that image which St Paul uses for the Christian life – new creation.

So the beginning of Christian life is a new beginning of God's creative work. And just as Jesus came up out of the water, receiving the Spirit and hearing the voice of the Father, so for the newly baptized Christian the voice of God says, 'You are my son/daughter', as that individual begins his or her new life in association with Jesus.

In the tradition of the Christian East especially, when the baptism of Jesus is shown in icons you will usually see Jesus up to his neck in the water, while below, sitting under the waves, are the river gods of the old world, representing the chaos that is being overcome. So from very early on baptism is drawing around itself a set of very powerful symbols. Water and rebirth: rebirth as a son or daughter of God, as Jesus himself is a son; chaos moving into order as the wind of God blows upon it.

So it is not surprising that as the Church reflected on what baptism means, it came to view it as a kind of restoration of what it is to be truly human. To be baptized is to recover the humanity that God first intended. What did God intend? He intended that human beings should grow into such love for him and such confidence in him that they could rightly be called God's sons and daughters. Human beings have let go of that identity, abandoned it, forgotten it or corrupted it. And when Jesus arrives on the scene he restores humanity to where it should be. But that in itself means that Jesus, as he restores humanity 'from within' (so to speak), has to come down into the chaos of our human world. Jesus has to come down fully to our level, to where things are shapeless and meaningless, in a state of vulnerability and unprotectedness, if real humanity is to come to birth.

This suggests that the new humanity that is created around Jesus is not a humanity that is always going to be successful and in control of things, but a humanity that can reach out its hand from the depths of chaos, to be touched by the hand of God. And that means that if we ask the question, 'Where might you expect to find the baptized?' one answer is, 'In the neighbourhood of chaos'. It means you might expect to find Christian people near to those places where humanity is most at risk, where humanity is most disordered, disfigured and needy. Christians will be found in the neighbourhood of Jesus – but Jesus is found in the neighbourhood of human confusion and suffering, defencelessly alongside those in need. If being baptized is being led to where Jesus is, then being baptized is being led towards the chaos and the neediness of a humanity that has forgotten its own destiny.

I am inclined to add that you might also expect the baptized Christian to be somewhere near, somewhere in touch with, the chaos in his or her own life – because we all of us live not just with a chaos outside ourselves but with quite a lot of inhumanity and muddle inside us. A baptized Christian ought to be somebody who is not afraid of looking with honesty at that chaos inside, as well as being where humanity is at risk, outside.

So baptism means being with Jesus 'in the depths': the depths of human need, including the depths of our own selves in their need – but also in the depths of God's love; in the depths where the Spirit is re-creating and refreshing human life as God meant it to be.

Sharing in the life and death of Jesus

If all this is correct, baptism does not confer on us a status that marks us off from everybody else. To be able to say, 'I'm baptized' is not to claim an extra dignity, let alone a sort of privilege that keeps you separate from and superior to the rest of the human race, but to claim a new level of solidarity with other people. It is to accept that to be a Christian is to be affected – you might even say contaminated – by the mess of humanity. This is very paradoxical. Baptism is a ceremony in which we are washed, cleansed and re-created. It is also a ceremony in which we are pushed into the middle of a human situation that may hurt us, and that will not leave us untouched or unsullied. And the gathering of baptized people is therefore not a convocation of those who are privileged, elite and separate, but of those who have accepted what it means to be in the heart of a needy, contaminated, messy world. To put it another way, you don't go down into the waters of the Jordan without stirring up a great deal of mud!

When we are brought to be where Jesus is in baptism we let our defences down so as to be where he is, in the depths of human chaos. And that means letting our defences down before God. Openness to the Spirit comes as we go with Jesus to take this risk of love and solidarity. And that is why, as we come up out of the waters of baptism with Jesus, we hear what he hears: 'This is my son, this is my daughter, this is the one who has the right to call me Father.' The Spirit, says St Paul, is always giving us the power to call God Father, and to pray Jesus' prayer (Galatians 4.6). And the baptized are these who, going with Jesus into risk and darkness, open themselves up to receive the Spirit that allows them to call God Father.

So what else do you expect to see in the baptized? An openness to human need, but also a corresponding openness to the Holy Spirit. In the life of baptized people, there is a constant rediscovering, re-enacting of the Father's embrace of Jesus in the Holy Spirit. The baptized person is not only in the middle of human suffering and muddle but in the middle of the love and delight of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. That surely is one of the most extraordinary mysteries of being Christian. We are in the middle of two things that seem quite contradictory: in the middle of the heart of God, the ecstatic joy of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit; and in the middle of a world of threat, suffering, sin and pain. And because Jesus has taken his stand right in the middle of those two realities, that is where we take ours. As he says, 'Where I am, there will my servant be also' (John 12.26).

Growing out of that, the prayer of baptized people is going to be a prayer that is always moving in the depths, sometimes invisibly – a prayer that comes from places deeper than we can really understand. St Paul says just this in his letter to the Romans: 'The Spirit helps us in our weakness ... that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words' (Romans 8.26). The prayer of baptized people is never just 'rattling off' the words at surface level. The prayer of baptized people comes from a place deeper than we can penetrate with our minds or even our feelings. Prayer in the baptized community surges up from the depths of God's own life. Or, to change the metaphor, you might say that we are carried along on a tide deeper than ourselves, welling up from God's depths and the world's.

The prayer of baptized people is a growing and moving into the prayer of Jesus himself and therefore it is a prayer that may often be difficult and mysterious. It will not always be cheerful and clear, and it may not always feel as though it is going to be answered. Christians do not pray expecting to get what they ask for in any simple sense – you just might have noticed that this can't be taken for granted! Rather, Christians pray because they have to, because the Spirit is surging up inside them. Prayer, in other words, is more like sneezing – there comes a point where you can't not do it. The Spirit wells and surges up towards God the Father. But because of this there will be moments when, precisely because you can't help yourself, it can feel dark and unrewarding, deeply puzzling, hard to speak about.

Which is why so many great Christian writers on the spiritual life have emphasized that prayer is not about feeling good. It is not about results, or about being pleased with yourself; it is just what God does in you when you are close to Jesus. And that of course means that the path of the baptized person is a dangerous one. Perhaps baptism really ought to have some health warnings attached to it: 'If you take this step, if you go into these depths, it will be transfiguring, exhilarating, life-giving and very, very dangerous.' To be baptized into Jesus is not to be in what the world thinks of as a safe place. Jesus' first disciples discovered that in the Gospels, and his disciples have gone on discovering it ever since.

One of the great privileges of my time as Archbishop of Canterbury was being allowed to go and see some of those places at close quarters where people live in dangerous proximity to Jesus; where their witness means they are at risk in various ways. And when you see people in places like Zimbabwe, Sudan, Syria or Pakistan living both in the neighbourhood of Jesus and in the neighbourhood of great danger, you understand something of what commitment to the Christian life means, the commitment of which baptism is the sign. But you see it also when you look at the lives of great saints whose path of contemplation has led them to deep inner desolation, loneliness and uncertainty (think of what Mother Teresa of Calcutta wrote in her diaries about the many years in which she felt practically no 'spiritual' comfort, only isolation and darkness). All this results from the upsurging life of the Spirit in the centre of our being, coming from the heart of God. Like the saints before us, we tread a dangerous path – which is also the path to life.

The path is both dangerous and life-giving for me as an individual believer – but not only for me. The other great truth about baptism is that it brings you into proximity not only with God the Father, not only with the suffering and muddle of the human world, but with all those other people who are invited to be there as well. Baptism brings you into the neighbourhood of other Christians; and there is no way of being a Christian without being in the neighbourhood of other Christians. Bad news for many, because other Christians can be so difficult! But that is what the New Testament tells us very uncompromisingly: to be with Jesus is to be where human suffering and pain are found, and it is also to be with other human beings who are invited to be with Jesus. And that, says the New Testament, is a gift as well as sometimes a struggle and an embarrassment.

It is a gift because in this community of baptized people we receive life from others' prayer and love, and we give the prayer and love that others need. We are caught up in a great economy of giving and exchange. The solidarity that baptism brings us into, the solidarity with suffering, is a solidarity with one another as well. It is what some Christian writers have called, in a rather forbidding word, 'co-inherence'. We are 'implicated' in one another, our lives are interwoven. What affects one Christian affects all, what affects all affects each one. And, whether as individual Christians or as individual Christian groups and denominations, we often find that hard to believe and accept. We find it hard to accept it as a gift – yet a gift is what it is. It means that the darkness that belongs in the baptized life is never my own problem exclusively. It is shared: how it is shared is very mysterious, and yet most of us who are baptized Christians can witness in one way or another to the fact that it works.

So baptism restores a human identity that has been forgotten or overlaid. Baptism takes us to where Jesus is. It takes us therefore into closer neighbourhood with a dark and fallen world, and it takes us into closer neighbourhood with others invited there. The baptized life is characterized by solidarity with those in need, and sharing with all others who believe. And it is characterized by a prayerfulness that courageously keeps going, even when things are difficult and unpromising and unrewarding, simply because you cannot stop the urge to pray. Something keeps coming alive in you; never mind the results.

Alex, that line is brilliant, life-giving: "The best way to fight the anti-Christ... is to be like Christ." Amen. Amen. Amen. YES!

ReplyDelete"Christians will be found in the neighbourhood of Jesus – but Jesus is found in the neighbourhood of human confusion and suffering, defencelessly alongside those in need. If being baptized is being led to where Jesus is, then being baptized is being led towards the chaos and the neediness of a humanity that has forgotten its own destiny.... you don't go down into the waters of the Jordan without stirring up a great deal of mud!" Thanks, Alex (and Rose, Faith and Caleb) for the ways you walk, with us, in our chaos.